Health x Wellness

That Tired Feeling? Why a Global Plan to Fix It Needs a Major Rethink

It’s that persistent, bone-deep exhaustion that coffee can’t fix.

Officially, it’s called anaemia, a condition that develops when your body doesn’t have enough healthy red blood cells to ferry oxygen around. And it’s not just a personal problem—it’s a global one, affecting nearly two billion people. For years, it has quietly undermined maternal health, child survival, and even economic growth.

Back in 2015, the United Nations set an ambitious goal: to cut anaemia in women of childbearing age by half by 2030. It sounded like a solid plan. Yet, nearly a decade later, most countries are nowhere near hitting that target.

Now, researchers from Singapore’s Duke-NUS Medical School, working with an international team, have published a study in The Lancet Haematology that explains why. Their findings suggest the world needs to get smarter, not just more ambitious.

The Problem with a One-Size-Fits-All Target

The core issue, the study argues, is that a single, universal target doesn’t work for a problem with complex, local causes. While iron deficiency is the main culprit, factors like other nutrient shortages, chronic diseases, or infections like malaria and hookworm play significant roles depending on the region.

Assistant Professor Robin Blythe from Duke-NUS, who led the study’s economic modelling, puts it plainly: “A one-size-fits-all approach to anaemia does not work. Countries face very different challenges, from poverty and infectious diseases to food shortages. These realities are often overlooked in global health targets. We need goals that are ambitious yet realistic—and tailored to each country’s needs and resources.”

The research reveals that the global goal of a 50 percent reduction simply isn’t feasible for most nations with the current tools and funding available. In many low- and middle-income countries, the recommended interventions are either unavailable, too expensive, or not widely used.

A Smarter, Tailored Strategy

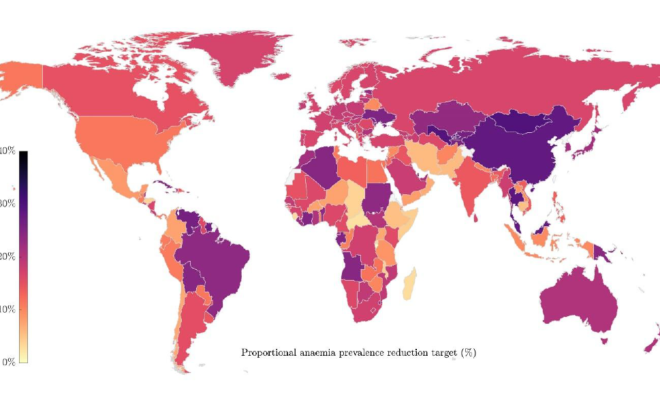

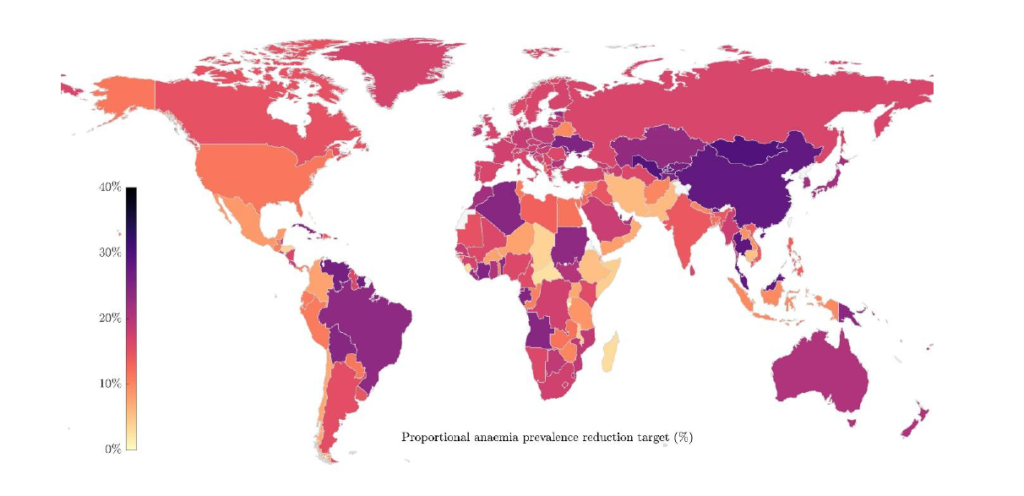

Instead of a blanket goal, the team modelled realistic, country-specific targets for 2030. They analysed each nation’s anaemia rates, healthcare capacity, and what it could afford to spend on public health measures like fortifying staple foods, providing iron supplements, and preventing malaria during pregnancy.

The results show a stark contrast. Malaysia, for example, could realistically aim for a 28 percent reduction, while neighbouring Indonesia is projected to achieve only a 9 percent reduction due to constraints on its healthcare spending.

Singapore, with its strong health system and high coverage for antenatal care, could achieve a 25 percent reduction. Here, most anaemia cases are mild, and the country is well-positioned to fortify staple foods and improve the uptake of iron supplements for pregnant women.

“By focusing on fortifying staple foods with iron and improving the uptake of supplements during antenatal care, the country can achieve real reductions in anaemia while using resources efficiently,” said Asst Prof Blythe.

These variations underscore the need to move away from uniform global targets and instead direct resources where they will have the greatest impact.

Better Data and Realistic Ambition

A key part of the problem is a lack of detailed information. The study calls for better data systems that don’t just count how many people have anaemia, but also track its specific causes within different populations.

But does setting more achievable goals mean giving up? Asst Prof Blythe argues it’s the opposite.

“When targets are set too high and countries fail to meet them, it can create frustration and even discourage continued efforts. Our approach provides a clear, data-driven way to set targets that reflect what each country can realistically achieve with current tools. This way, we can still drive progress while being honest about what is possible.”

The researchers are now sharing their findings with the World Health Organisation, hoping to influence a more evidence-based approach to future global health targets. It’s a call for a more practical, intelligent path forward—one that could finally make meaningful progress against a condition that holds billions of people back.