The Gen XY Lifestyle

What is sustainable Universal Health Coverage 2.0?

The “UHC 2.0: Charting A Course To Sustainable Healthcare And Financing In The Asia-Pacific” white paper explains gaps in current healthcare delivery and financing models and solutions for sustainable solutions.

The “UHC 2.0: Charting A Course To Sustainable Healthcare And Financing In The Asia-Pacific” white paper was published by KPMG Singapore and Sanofi, along with support from the World Economic Forum.

It explains gaps with the current healthcare delivery and financing models, and solutions towards ensuring that healthcare delivery and financing designs in Asia Pacific can sustain themselves. The white paper introduces and defines “Universal Health Coverage 2.0” (UHC 2.0). This is a model that can ensure healthcare delivery and financing designs can sustain themselves.

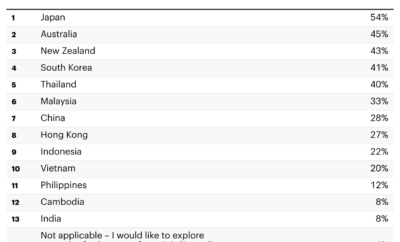

The Asia-Pacific region is home to about 60 per cent of the world’s population, yet it’s faced with multiple challenges when it comes to delivering and financing healthcare systems. With ageing populations, the rise in communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic providing the impetus, healthcare providers should look towards adopting more sustainable and long-term modes of financing and delivering healthcare.

Guillaume Sachet, Partner, Advisory, KPMG in Singapore

The white paper homes in on three care pathways – life-course immunisation, diabetes management and rare diseases – as these reflect the most pressing healthcare needs currently. Along with identification of the challenges, the white paper also shares recommendations and solutions. These are attributed to experts across the region.

The solutions fall into two main categories, that is, improving health delivery and innovating health financing.

- To improve health delivery, the white paper shares about strengthening infrastructure, including for digital health; building capacity through upskilling and advocating for consumer behaviour change.

- Innovation in health financing can involve a move away from traditional tax or employer-funded schemes for investment in social services to new models such as crowdfunding, tapping into debt financing and even incentivising consumers to share accountability.

Both these solutions can be accomplished across areas such as life-course immunisation, diabetes management and rare diseases.

Ada Wong, Asia Public Affairs Lead, Sanofi shares more about UHC 2.0 with the Active Age.

the Active Age (AA): Can you expand on the concept of UHC 2.0?

Ada Wong (AW): Universal Health Coverage 2.0 (UHC 2.0) is a proposed model of healthcare by a core research team comprising the World Economic Forum, KPMG and Sanofi, which recognises the need to increase efficiency, optimise limited resources and ensure sustainability of healthcare systems.

The Asia Pacific region is faced with multiple challenges, such as increasing communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as an ageing population. To ensure that our children and grandchildren obtain a high level of healthcare, the research team foresees that current delivery and financing models will not be able to address existing and future challenges and that these models should be reformed.

For example, solely funding the public healthcare system with allocation from taxes will not be sustainable in the near future given the rise in ageing populations and the increase in the informal workforce such as gig workers, especially in developing countries across the region.

AA: What is the link between financing models and better healthcare and UHC 2.0?

AW: As populations age, the number of people in the workforce decreases, which generates low levels of tax to fund healthcare systems. The Asia Pacific region is also facing a growing level of informal workforce, inaccessible and unaffordable private insurance and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated the gaps in care for other diseases.

To ensure sustainable and inclusive healthcare systems that address these challenges, more creative financing strategies, such as crowdfunding, tax incentives for preventative health (e.g. health screenings and active lifestyle programs) and ‘sin’ taxes (e.g. taxing sugary drinks), as well as delivery models that leverage on digital health and incentivisation should be explored.

Diversifying and developing creative ways for healthcare to be delivered and funded will prevent healthcare systems from being over-burdened and under-funded, while shifting resources to the most pressing areas.

By improving efficiency and cost-effectiveness, governments can then reinvest the saved resources and funds back into the healthcare system to further improve the quality of care and coverage for all. This benefits individuals, society and healthcare systems in the long-term, as we move towards more sustainable, resilient and inclusive health systems.

AA: Amongst the 3 pathways described in the white paper, is any particular pathway critical and by achieving success in this pathway, will help achieve progress with the other pathways?

AW: The three pathways described in the white paper – life-course immunisation, diabetes management and rare disease – reflect the most pressing needs, as identified by the core research team, comprising of World Economic Forum, KPMG and Sanofi and learnings from these pathways could be applied to other diseases.

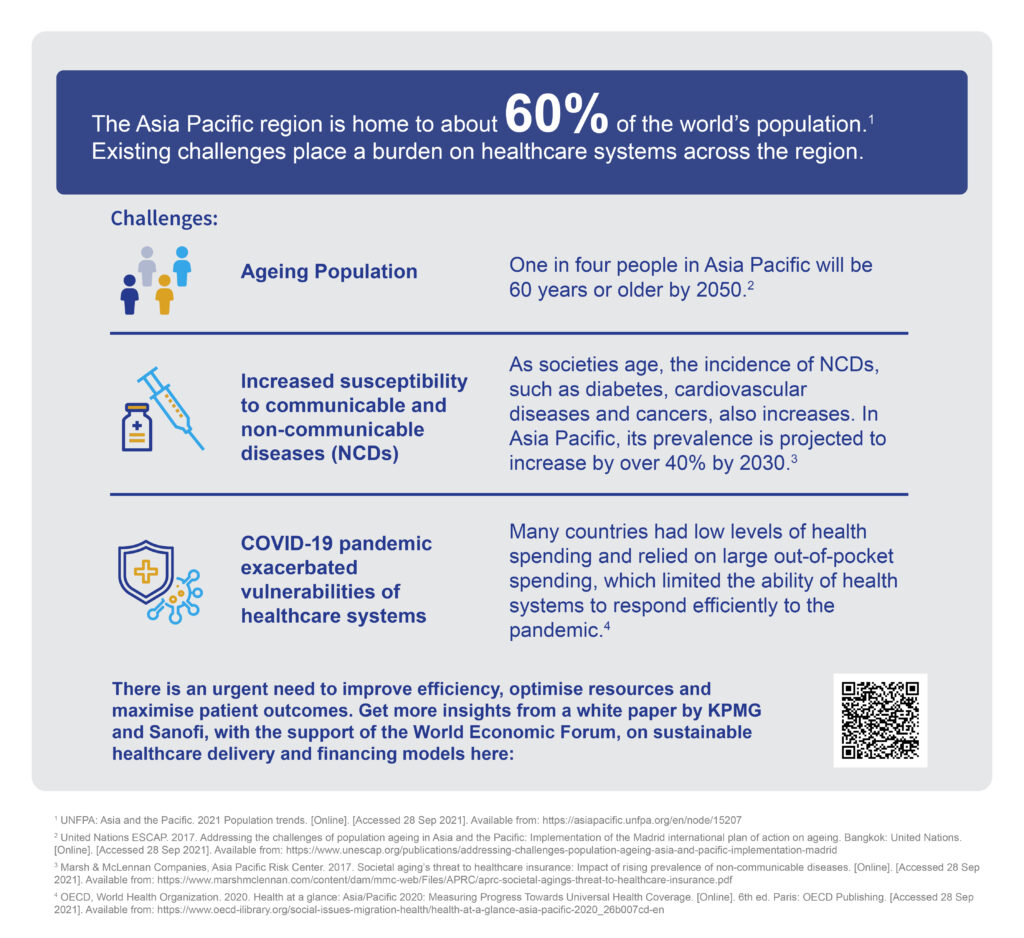

While all three areas are important, we know that preventative health is a critical component. The white paper also advocates allocation of more funds to areas in healthcare with maximum impact, which is preventative health such as life-course immunisation. Life-course immunisation, which is immunisation throughout the course of one’s life (from children to adults to older adults), is one of the most cost-effective prevention methods of illnesses, which also helps reduce the risks and complications of related health conditions.

AA: How relevant are public-private partnerships in helping accomplish progress with the pathways?

AW: Increased public-private partnerships are important for better knowledge sharing to understand the current healthcare landscape and then to design better interventions that is inclusive for all, as well as pooling of resources and expertise.

For example, even though private insurance is a common method of healthcare financing, this option is often inaccessible, especially for those in developing countries, where the penetration rate is often less than 5 percent.

However, reduced premium payments for policyholders that are highly engaged with their health, such as attending annual check-ups, or offering comprehensive digital wellness programmes and using reward points and wearable trackers to motivate healthier lifestyles could be designed collaboratively between public and private sectors.

AA: Can you share an example where a PPP has moved the needle with any of the pathways?

AW: In Japan, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry piloted a program for healthcare social impact bonds – a type of public-private partnership where investors are paid based on the success of pre-defined social outcomes – to prevent dementia, followed up diabetes prevention and colorectal cancer screening. In 2017, the government launched a grant programme for its research and development. Major banks, such as SMBC and Mizuho Bank invested in these social impact bonds, which generates the innovation and momentum needed to trial new approaches to gather the cost-benefit analysis and support for such creative financing approach.

AA: By embarking on preventive healthcare models, how can we explain its value to publics that have not yet encountered a critical or chronic health condition?

AW: Even though preventative healthcare such as life-course immunisation is recognised as one of the most cost-effective solutions available, the uptake rates of vaccination beyond childhood across Asia Pacific has remained low.

In Singapore, for example, despite a World Health Organization (WHO) target of 75 percent, fewer than 20 percent of people over the age of 50 get flu vaccines. Such is the importance of prevention that Mr Ong Ye Kung, Minister for Health of Singapore highlighted the low uptake of flu vaccines in Singapore and hoped that the COVID-19 pandemic would increase awareness of the benefits of vaccination for other infectious diseases.

Vaccines such as the flu vaccine don’t just help to prevent the flu itself but can prevent related complications such as heart attacks and pneumonia. While the risk of developing these complications is higher in the elderly as well as people with existing health conditions such as diabetes (people living with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalised, with the mortality varying between 5 percent and 15 percent ), even healthy adults are at risk – studies show that deaths due to influenza is around 10,000-30,000 annually1. Public education and awareness campaigns are important in being able to communicate these risks as well as the role of vaccination through relevant and tailored channels.

Preventative healthcare, including vaccination throughout the course of one’s life should be seen as a long-term investment that reduces the severity of other communicable and non-communicable diseases, relieving the already-stressed healthcare systems, as well as providing positive economic outcomes, as patients would spend and use less of the limited healthcare resources.

References:

- 1 – Kesavadev J, Misra A, Das AK, Saboo B, Basu D, Thomas N, et al. (2012). Suggested use of vaccines in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 16(6):886-893.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash