The Gen XY Lifestyle

How can a plant-based protein approach lead to a climate-safe outcome?

Asia Research and Engagement (ARE) has released a report titled ‘Charting Asia’s Protein Transition’ focused on the role of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions related to protein consumption and production across the ten largest Asian markets.

These 10 largest markets in Asia include China, India, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Indonesia. The study seeks to shed light on the significant impact of animal protein production on greenhouse emissions. It also models pathways needed for protein security and climate safety in Asia. This will help to pave the way for a more sustainable, healthy and resilient food system.

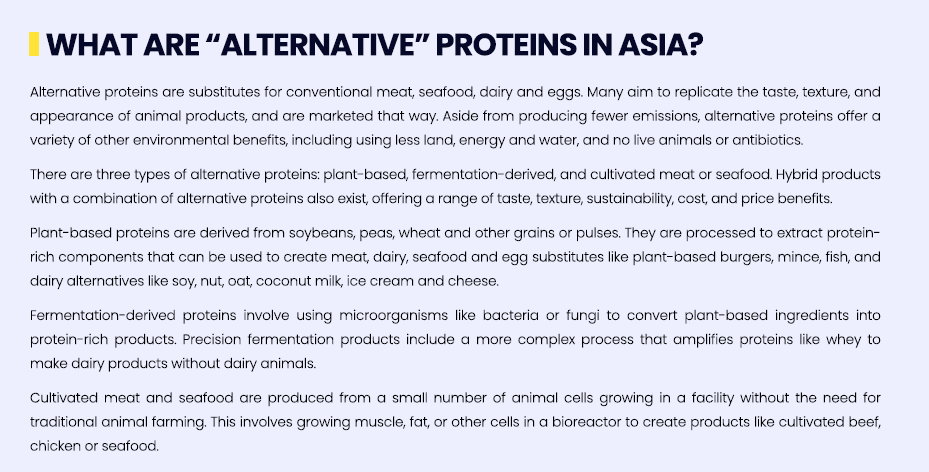

The report shares if we want to ensure climate-safety by 2060, certain mitigation measures will be necessary. For example, consumers will have to accept an increase in consumption of aternative proteins, while policy makers have to consider means of eliminating deforestation and reducing industrial animal production.

We discuss the report and its findings with Kate Blaszak, Director, Protein Transition, Asia Research & Engagement.

the Active Age (AA): What is the background of the study, and why did you choose to focus on animal protein production as a key factor impacting greenhouse emissions?

Kate Blaszak (KB): The background of this study stems from the pressing need to address the intertwined challenges of climate change, food security, and sustainable development in Asia. As Asia is a major contributor of over half of the world’s terrestrial animal protein and farmed seafood, we want to re-examine the relationship between the region’s protein consumption, and climate emissions (as part of the environmental impacts of the protein system).[1]

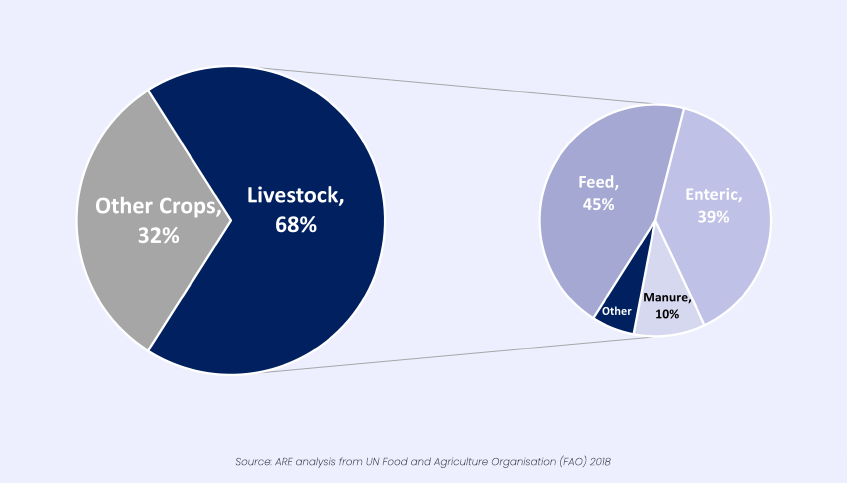

Animal protein production is ARE’s focus due to its substantial contribution to greenhouse gas emissions[2], largest driver of deforestation, biodiversity loss, pollution and greatest use of antibiotics, land, water, and animals, among other negative environmental and social impacts. With this study, we wanted to examine the link between Asia’s consumption and demand for animal protein, the intensification of animal production, and the resulting contribution to the climate crisis. Most importantly, we wanted to explore solution pathways and opportunities for 10 of Asia’s largest markets to achieve protein security and climate-safety, contributing to the Paris Agreement 1.5C goal via sustainable growth.

We wanted to stimulate the enablers of this transition: financial institutions, policy makers and food companies in the region. By focusing on protein projections and alternative scenarios, we aimed to uncover actionable insights that support a transformative shift towards a more balanced, healthy, and climate-friendly protein system.

AA: Based on the study, what is the key impact of animal protein production on greenhouse emissions?

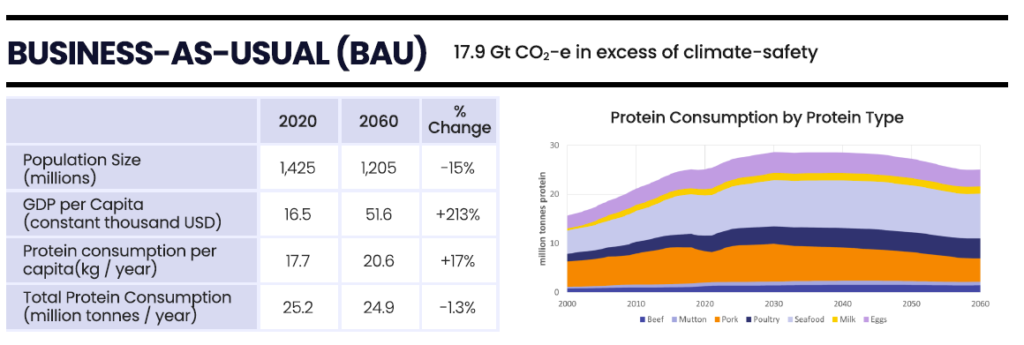

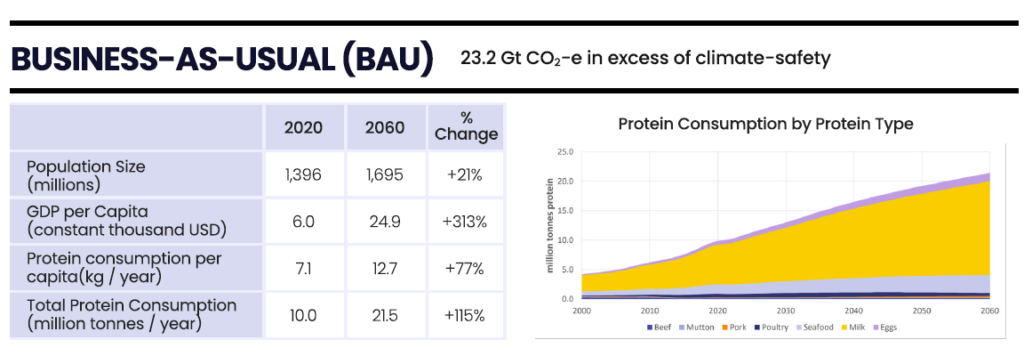

KB: We’ve learnt from the study that if the projected growth in Asia’s consumption of animal protein is left unchecked, it will lead to a substantial increase in emissions. Business as Usual (BAU) production is not aligned with the Paris Agreement Goals and National Determined Contributions. It will incur significant excess emissions with the climate-safety (derived from the Science Based Target initiative). You can refer to the 10 market summaries with almost 18Gtonnes excess GHG for China, for example. We will not avert climate crisis if the protein system is not transformed.

As such, the sheer scale of animal production, particularly in emerging economies, will amplify the environmental strain, as more land is cleared for feed, farming and more natural resources are consumed. This is particularly due to deforestation, in many countries such as China, South Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia and others importing deforestation-linked soy or beef from South America.

Markets like Singapore that import animal protein (or feed) from such countries and South America, are also culpable of contributing to deforestation. The report also finds that intensive animal production must peak now in some cases (Japan, Thailand), and by 2030, if not sooner in the other markets. Consumers, companies, banks, and other stakeholders need to consider these major systemic risks, before allocating more capital, lending, and investment into BAU protein systems. Consumers can best contribute with more sustainable protein purchases! I have elaborated more on this below.

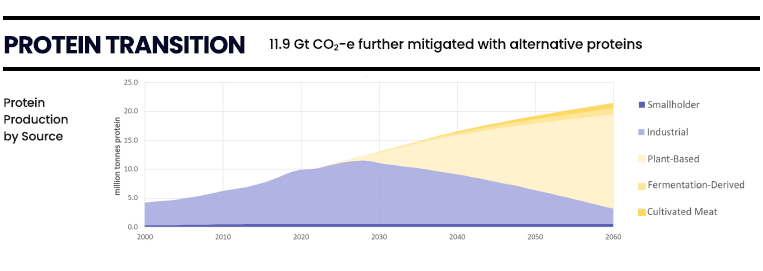

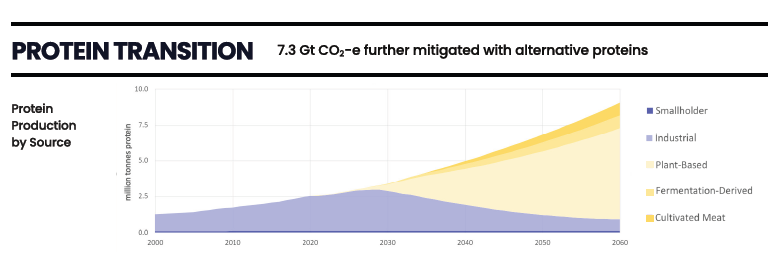

As a result, the report emphasises the urgent need to curb these emissions by shifting away from heavy reliance on conventional animal protein and gradually move towards more sustainable alternatives – with on average a 12 percent contribution to protein production by volume by 2030, and between 30-90 percent of protein volume by 2060, depending on the specific market. We (and many other scientists) see this as part of a sector strategy to combat climate change and achieve a more climate-resilient food system.

AA: What is the definition of climate safety we are seeking to achieve in Asia?

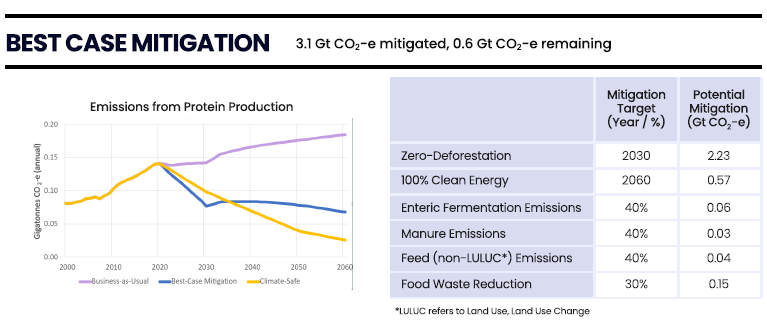

KB: The definition of climate safety refers to the goal of aligning the region’s protein system with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. This is quantified with parameters by the Science Based Target initiative for Food, Land and Agriculture (SBTi FLAG) released in September 2022.

This entails a 72 percent reduction in emissions by 2050, against a 2020 baseline, aiming to limit global warming to no more than 1.5°C, a critical threshold of irreversible climate change impacts.

In the context of the report, achieving climate safety in Asia’s protein system involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 72 percent by 2060, to accommodate China’s timeline. This would mean that Asia would require a significant shift towards sustainable protein sources on top of a substantial reduction in emissions from more responsible animal agriculture.

In most Asian markets, our report shows the following:

- Peaking industrial production now or by 2030 – so starting to decline consumption, investment, lending, and growth of industrial production.

- Setting targets to eliminate deforestation in protein supply chains, among other mitigations.

- Growing the share of alternative protein produced and consumed: plant, fermentation, or cell-based proteins (aka cultivated meat) substantially; and/or retaining substantial traditional plant-based protein sources.

AA: Why would the ‘business as usual’ model not work (to achieve climate safety)?

KB: The ‘business as usual’ model, whereby it is characterised by the continued reliance on conventional animal protein production and consumption practices, would not work to achieve climate safety due to several critical reasons as outlined in the report:

- Greenhouse gas emissions: Conventional animal protein production is associated with significant greenhouse gas emissions, including methane and nitrous oxide, which are potent contributors to global warming. Scaling up this model would lead to a substantial increase in emissions, making it incompatible with the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement.

- Deforestation and land use: The ‘business as usual’ model would perpetuate deforestation and land conversion for agricultural purposes (domestically and abroad) which will further exacerbate GHG emissions. The clearing of forests to create grazing land or to cultivate feed crops for animals is the largest driver of deforestation, globally.

- Strain on natural and other resources: Industrialised animal agriculture requires extensive resources, such as land, water, antibiotics, fertilisers, and feed. Hence, expanding this model would place additional stress on these resources which are already scarce and contribute to further environmental degradation. The planetary boundaries for Nitrogen and Phosphorus are already exceeded, and we are approaching boundaries for climate, water, air pollution and biodiversity loss.

- Impact on health: Continuing with high levels of animal protein consumption can contribute to health issues, including diet-related diseases. (Please see the section of meat and seafood consumption, against EAT Lancet Commission recommendations: China, South Korea, Japan, Singapore*, Malaysia, and Vietnam where at least countries consume substantially more meat and seafood than is considered healthy and sustainable.[3]) Additionally, the reliance on industrial animal production leads to increasing impact and risks of antimicrobial resistance and diseases transferred from animals to humans.

Given these challenges, we would need a transformative shift towards more sustainable i.e. alternative protein sources in order to align with climate safety goals and to ensure the long-term viability of the food system.

AA: In the report, some solutions or pathways modelled that can contribute to climate safety include increasing market share of alternative proteins, reducing industrial animal protein production, eliminating deforestation, etc. In your opinion, how would countries and industries seek to do so?

KB: We highlight that the approaching COP28 will include food on the agenda for the first time. Countries and industries can reduce climate emissions and pursue several strategies to achieve the modelled solutions and pathways outlined in the report for achieving climate safety through a protein transition:

- Policy and government regulation: Governments can enact legislation and strengthen policies that incentivise the production, consumption, and investment in alternative protein sources. This can include tax incentives, policies[4], avoiding damaging subsidies[5], and regulations that promote sustainable practices and discourage emissions-intensive activities and systems. For instance, the Government of Taiwan enacted a Bill, earlier this year to encourage more consumption of plant-based proteins by government and other intuitions. While Singapore could do something similar to promote more healthy and sustainable protein consumption, it currently helps to drive some of the solutions. The Singapore government has incentivised loans, rental and supports startups and regulatory processes for novel proteins. In fact, Singapore was the first country to approve the sale of a cultivated meat product in December 2020. Additionally, governments can also implement regulations to eliminate deforestation and promote responsible importation, sourcing, and financial lending – all of these efforts would help play a significant role in helping to achieve climate safety through a responsible and sustainable Protein Transition.

- Research and innovation: As investment in research and development is essential for advancing alternative protein technologies, improving their scalability, taste and reducing production costs, governments and private industries can collaborate to fund research initiatives that accelerate the development of plant-based, fermentation-derived, and cultivated meat or seafood products.

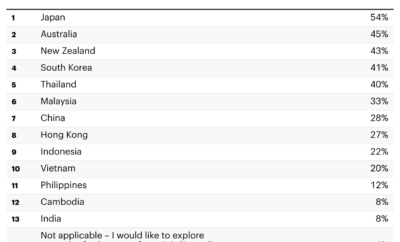

- Consumer awareness and education: Raising consumer awareness about the environmental and health benefits of alternative proteins can drive demand for these products. Public campaigns, education programs, and labelling initiatives can encourage consumers to adopt healthier and more sustainable dietary patterns, including reducing meat consumption and incorporating more plant-based foods into their diets. We have seen a significant uptake and increase in sales in Singapore with alternative proteins. Retailers can also assist, and studies show that suitable placement, promotion and labelling can significantly increase sales of plant-based proteins ARE speaks to this in a recent article and supermarket scorecard (used in Thailand) available for reference here.

- Collaboration and partnerships: Governments, industries, research institutions, and non-governmental organizations must collaborate for a successful transition. Multi-stakeholder partnerships can help to foster knowledge sharing, technology transfer, and the development of best practices and upscaling.

- Financial support: Financial institutions and investors can play a vital role by directing funding and investments towards more responsible and sustainable e.g. alternative protein projects. For example, the development of financial products specifically designed to support protein transition initiatives can help accelerate the adoption of these technologies, while establishing sustainability frameworks that do not lend to customers that perpetuate deforestation, unlimited growth, and emissions from industrial production, requiring them to have science- based targets, strategies, and practical pathways towards net zero outcomes.

- Supply chain transparency: Industries can enhance supply chain transparency by adopting digital traceability systems (across the supply chain) that ensure responsible sourcing of ingredients and reduce the risk of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and other impacts on natural resources. Having such transparency and traceability in place can also build consumer trust and support ethical and sustainable practices and purchasing.

By implementing a combination of these strategies and fostering a supportive ecosystem, countries and industries can effectively pursue the pathways modelled in the report and make significant progress toward achieving climate safety and protein security through a protein transition.

Images and visuals attributed to Asia Research and Engagement.

References cited in the interview:

[1] Many academics had modelled the global GHG emissions of BAU. Many also had modelled the various GHG footprints of various proteins. No one had modelled what the pathway for climate-safety and protein security for Asia (without carbon credits). GINA report is also useful.

[2] Animal production is the second largest contributor to GHGs globally: with at least 15% of global emissions, and half the global food system emissions. Various sources: FAO, Our world in Data etc.

[3] SFA notes; In 2021, one person in Singapore consumed an average of around 390 eggs, 100 kg of vegetables, 22 kg of seafood, 62 kg of meat (i.e. chicken, pork, beef, mutton). EAT Lancet recommends no more than 26kg of meat and seafood per year, or weekly consumption as detailed on page 30 of the report.

[4] We’ve seen a precedent with Taiwan’s new policy and Bill announced earlier this year

[5] The 2023 World Bank report – Detox Development – shows how conventional subsidies have continued to deliver environmental destruction, and outlines some necessary changes.